Simultaneous Initiation

A lot of the internal tools at my workplace use Redis for interprocess communication. The user runs a Redis server on their machine, and our programs connect to it on startup. It works well—Redis lets you set up arbitrary Pub/Sub channels, which is an easy way to address messages using names instead of the IP address and port of every recipient.

Except that when I was working on the system a year ago, every week a different programmer would summon me to their desk with an impenetrable assertion failure trapped in the debugger. Our client programs send a CLIENT SETNAME command immediately after connecting to associate a debug name with their session, and the Redis server seemed to occasionally respond with an array containing the CLIENT command itself (instead of the expected response, OK).

An interesting feature of the Redis protocol is that the wire format you use to send commands to the server is exactly the same as the multi-bulk reply format. So if some unknown gremlin redirects a client’s message back at itself, the client library will happily parse it and return it as a string array to the application. But we know that the SETNAME command isn’t supposed to return an array, so our application immediately asserts if it gets such a response.

Like all the best bugs, this one was not immediately reproducible. All I could do was apologize to my colleague, ask them to let me know if it happened again, retreat to my desk, and try to muddle through it. Maybe there’s a bug in the Windows Redis server that occasionally gets its wires crossed and sends a client’s own message back to itself… or maybe there’s a bug in our custom version of hiredis…

Into the crucible

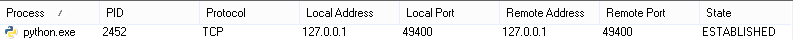

I got lucky. Another user reported an issue: the interprocess communication system simply wasn’t working at all on his machine. When I looked at his box, I noticed that our monitoring tool was continually restarting the Redis server process. Looking at the server log revealed the first clue: the server wasn’t starting up because another process was already using the port that it was configured to use. The TCPView program (from the unfathomably useful Sysinternals suite of utilities for Windows) revealed that something very strange was going on: one of our applications had successfully made an outgoing TCP connection to localhost on the port that Redis uses, but the socket wasn’t connected to a Redis server—it was connected to itself.

[An attempt at poetry demonstrating the author’s progress through the five stages of grief has here been omitted. — Ed.]

When I came to my senses and picked myself up off of the floor, I decided that my first step was to get familiar with the bug’s modus operandi. Not being a network programmer normally, I wasn’t sure if a socket is supposed to be able to connect to itself. Let’s ask our listeners:

import socket

sock = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM, socket.IPPROTO_TCP)

sock.bind(('127.0.0.1', 49400))

sock.connect(('127.0.0.1', 49400))On my Mac, that snippet of Python raises socket.error: [Errno 22] Invalid argument. On my Windows machine, it succeeds, and the socket can send data to itself. Now there’s a curiosity: a TCP socket that accepted an incoming connection without having ever been the LISTEN state:

Not satisfied with mere empirical evidence, I went straight to the source. Sure enough, in the bowels of the XNU kernel used by Mac OS X, there’s code in the tcp_connect function to fail with an EINVAL error if the socket’s local address and port are exactly the same as the remote address and port passed to the connect() function:

if ((inp->inp_laddr.s_addr == INADDR_ANY ? laddr.s_addr :

inp->inp_laddr.s_addr) == sin->sin_addr.s_addr &&

inp->inp_lport == sin->sin_port) {

error = EINVAL;

goto done;

}At first blush it seems like it would take extra work for WinSock to implement this pitfall: you don’t just get a weird broken socket, you get a fully functional socket that just happens to loop back to itself. If it was as simple as the Windows kernel omitting this check, you could get a socket that routes TCP packets to itself, but you haven’t managed to bypass the TCP stack itself. The first connect() should cause the socket to send a SYN packet and transition to the SYN-SENT state, at which point I would expect it to receive its own SYN packet and abort. So who decided that a reflexive TCP socket was useful enough to implement?!

Stack Overflow provided the answer: the TCP state diagram actually specifies a state transition for receiving a SYN packet while in the SYN-SENT state, as part of the procedure for two sockets simultaneously connecting to each other, which is known variously as “simultaneous initiation” and “simultaneous open.” So there is actually prescribed behavior allowing two different sockets, neither of which has called listen(), to establish a single connection from one to the other. Of course, you normally have to be on very good terms with your opposite number to get this to happen: by default a socket’s local port number is automatically assigned, so both sockets have to manually bind() themselves to agreed-upon ports (and if another process has already taken that port on your network interface, you’re screwed).

That is presumably the procedure that has been co-opted into allowing a socket to connect to itself—the process is entirely symmetric and works just as well if the packets rebound off of a solid wall right back at the sender. In my opinion, it’s not within the spirit of the law—it’s hardly “simultaneous” with only one socket!—but it does explain why TCP doesn’t trip over its own feet.

“I suppose you’re wondering why I’ve called you all here…”

I can live with the notion that if I explicitly ask a socket to connect to itself, WinSock will allow it. I can’t think of any use for this peculiarity, especially since it isn’t portable, but perhaps someone else can. But while RFC-lawyering passes the time, it doesn’t help with the real issue: I never request this useless loopback socket, but in some circumstances I get one anyway.

There’s only two more pieces of information that you need to crack this locked-room mystery. First, the automatically-assigned local port that the OS assigns if you never call bind() (or if you call bind() and pass 0 as the port number) is called an ephemeral port, and Windows by default allocates this port number from the recommended 49152–65535 range.

Second, our tool code attempted to connect to the Redis server every 200 milliseconds if it didn’t have a connection. I chose that rather aggressive rate as a workaround for a previous problem we had where Redis’s output buffer for our connection would fill up faster than we could empty it, causing the server to abort the connection. Tweaking the buffer size and transferring less data was the real fix for that issue, but I also wanted to guarantee that the connection was reestablished as soon as possible.

So if the Redis server happened to not be running, the client would attempt to connect to it and fail, but the client socket would still have an ephemeral port number allocated for it. And 200ms later it tries again with a new socket, which gets a new port number. And because we changed from the default Redis port to one in the ephemeral port range, the socket is eventually assigned the very port number that it’s trying to connect to, and the connection succeeds even though the server is not running.

In fact, on both Windows and Mac, ephemeral port numbers are allocated sequentially, not randomly. It takes less than an hour for a process with a 200ms period to try every single ephemeral port—and when the problem manifests, it won’t reproduce for another hour. Only the misbehaving client which kept a reference to the “successful” socket and subsequently prevented the real Redis server from starting made the problem easy to spot (mostly because it forced me to learn that TCPView exists).

To make sure that this was indeed the problem, I wrote a Python script which allocates sockets until the system-wide ephemeral port gets near a target number, and tries to connect to it (without explicitly calling bind()). I’ve used it to make the issue with our tool reproducible on demand, and it also nicely exhibits the behavior difference between Windows and Mac.

To the pain

We ended up working around the issue by switching to a port number that is outside the ephemeral port range. Amusingly, as soon as we had hunted down all the places that this port number had proliferated, we discovered that the new port number we picked was already used by a chat client that a few people were using, so we had to change it again. I guess you can’t fight fate.